By Sarah Glassford

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains.

-from “Ozymandias,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

I cannot think about the politics of commemoration without remembering a famous poem I read in one of my undergraduate English courses. In “Ozymandias,” Romantic poet Percy Shelley reflects upon the transience of memory and the futility of commemoration by describing a ruined statue celebrating a ruler whose works are forgotten, the grandiose text on the remaining plinth at odds with the demise of the memory it was meant to inspire.

As Robert Rutherdale’s Hometown Horizons and David Macfarlane’s Danger Tree have demonstrated in different ways, the impact of the First World War was perhaps most profoundly felt by individuals at the community and family levels.[i] The intensity of this intimate impact carried over into post-war memorial efforts, as shown by a wide array of scholars including Jonathan Vance, Joy Damousi, and Jay Winter.[ii] It mattered very much where war memorials were placed, whom they honoured, what form they took, and who stood where at the dedication ceremonies; the process of commemoration was sometimes long, painful, and divisive, as each faction battled to assert its particular vision over those of others. Canadians avoided much of this animosity after subsequent conflicts by simply adding new dates and names (the Second World War, Korea, Afghanistan) to Great War memorials. One might be forgiven for assuming that the impulse to commemorate the Great War – as represented by the weathered stone memorials found at village crossroads, in town cemeteries, and on the lawns of provincial capitals across Canada – have long-since lost their ability to stir up discord.

One might also assume that the controversy surrounding the proposed “Mother Canada” statue in Cape Breton (discussed in previous ActiveHistory posts here, here, and here) stemmed from the size of the venture: a monolithic sculpture in a highly visible location in a cherished national park, which claimed to say something universal about an entire country’s experience of a major global conflict. And yes, these were all controversial aspects of the project. However, a recent commemorative controversy in a quiet corner of rural Prince Edward Island serves as a timely reminder that size, scope, and scale do not always matter, nor does the passage of a century. The issues raised in the clash of opinion over Malpeque’s “Plug Street” are much the same as those raised by the Mother Canada proposal, and both controversies echo the pitched battles of nearly a century earlier.

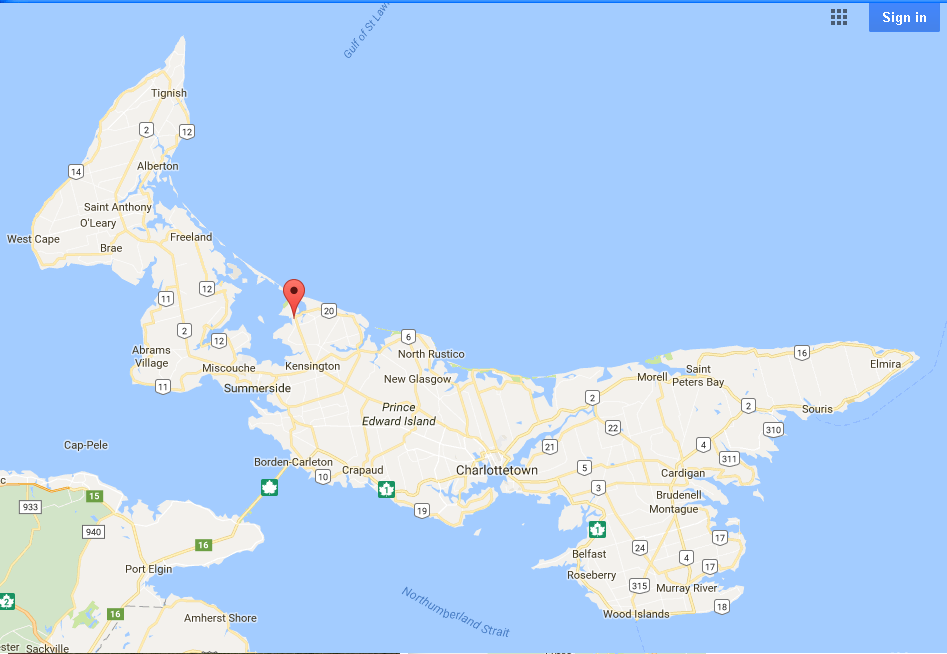

As shown in the map above, the inland rural crossroads of Malpeque is found in the northwest corner of Queen’s County, Prince Edward Island, not far from Malpeque Bay along the island’s north shore. For generations it has served a surrounding community of farmers and fishers – Malpeque oysters are its most famous export. Its central T-shaped intersection boasts a small but well-used community centre and an impressively-spired United Church. Clearly visible on the church lawn, as one approaches the junction of the T from all three directions, sits a tall stone and bronze war memorial. No simple cenotaph or solemn gravestone would do for the people of Malpeque after 1918. Instead, they commissioned a jaunty Canadian soldier in full kit, one hand on his rifle and the other proudly hoisting a furled flag in what could be read as either triumphant victory or plucky determination.

Malpeque’s 1921 Great War memorial, on the lawn of Malpeque United Church, September 2014. (All photographs by the author.)

Unveiled in 1921, the life-sized bronze soldier stands atop a tall stone pedestal, upon which are bronze plaques bearing the names of local men who died on active service. It is an attractive and well-executed memorial of its type, and its position at a major local crossroads, on the church lawn, speaks to its meaningful role at the heart of community life at the time of its creation. By all measures, the people of Malpeque discharged their commemorative duty well. Why, then, was a second Great War memorial dedicated in Malpeque 93 years later, just down the road from the first?

In November 2013, shortly before Remembrance Day, the Charlottetown Guardian announced that a new First World War monument would be placed in Malpeque. Its Plug Street site had been registered as a memorial in 2009, and federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Gail Shea (MP for Egmont, PEI) now announced on behalf of Veterans Affairs minister Julian Fantino that nearly $20,000 was earmarked for the creation of a sturdy granite memorial faced with Island stone. “Initiatives like these in our communities help send a vital message of remembrance and gratitude to our veterans … and provide an important opportunity to learn more about our proud military history,” Shea was quoted as saying. She added that it was only one of many efforts on the part of the (then-ruling) Conservative government to engage Canadians in acts of remembrance. The new memorial would specifically honour soldiers who fought in the region of Ypres during the Great War.[iii]

At this point, some readers may be thinking: “Well, not much to argue with there. Commemorate away.” Others may be musing along opposite lines, such as: “Couldn’t that $20,000 be better spent providing services to living veterans of Afghanistan or peacekeeping missions, with whom this same government was notoriously stingy?” But the actual opposition to the new Malpeque memorial arose for different reasons.

Project promoter and retired Colonel J. D. Murray contended that Plug Street in Malpeque was named for Ploegsteert in Belgium. It was an established fact that Canadian (and other English-speaking) soldiers stationed near Ploegsteert during the Great War had (as was common in trench slang) Anglicized/mangled the name to “Plug Street.”

Present-day Plug Street, Malpeque, looking toward Malpeque Bay from Route 20.

Although Murray admitted “we can never prove what veteran or veterans named this piece of roadway Plug Street,”[iv] he was convinced “This Plug Street here could not have been named by anyone other than a veteran of the Great War.”[v] By contrast, Murray’s most vocal opponent, Earle Lockerby (retiree, author specializing in Maritime history, and resident of nearby Darnley, PEI), considered the entire project “a government boondoggle and misuse of the public purse,” arising from “presumption and slipshod research.”[vi] It is important to note upfront that the conflict between them and their respective supporters may well have deeper (and/or unrelated) roots to which I, as a non-local and “Come-From-Away,” have no access. However, a significant portion of it played out in public, through a series of letters to the editors of the Charlottetown Guardian and Summerside Journal-Pioneer newspapers, and in related news reporting by the two papers and the local CBC station. These publicly-accessible texts offer telling glimpses into the contested terrain of commemoration.

Throughout the controversy, Murray’s authority seemed to stem from his military profession (he was a Canadian Forces veteran of several peacekeeping missions in the Middle East) and his role as Chair of the Commemoration Committee at Royal Canadian Legion Branch 9 in Kensington, PEI. He had previously succeeded in convincing the provincial government to rededicate the provincial highway, Route 2, as Veterans Memorial Highway, with accompanying memorial signage.[vii] By contrast, one of Lockerby’s opening salvos (at least in the public eye) was predicated upon his local connections to the area and the events being commemorated.

Jointly-signed letters to the editor from Lockerby, Mary (MacNutt) Werner, and Garth MacGougan began by stating: “We each grew up in the Malpeque area (one of us on Plug Street) and each has an uncle or great-uncle from the area who gave his life in the First World War.”[viii]

Bronze plaque honouring the local war dead, on the original Malpeque memorial. Note the Lockerby and MacGougan names listed.

“Nine men from the Malpeque area with the names MacGougan, Lockerby and MacNutt served in WWI, some at Ypres,” they added, bolstering their claim to a privileged position on the issue. The proposed memorial was “ill-conceived and [did] not do honour to First World War soldiers,” they wrote, because there was no conclusive evidence for the Ploegsteert connection and the memorial was based on “an aberrant process” in its earliest stages: namely, that the municipal Community of Malpeque Bay originally designated the street as a memorial in 2009 “without public consultation, without prior discussion at any council meeting and in the absence of a council motion.” Moreover, Malpeque already had a perfectly good war memorial, where they would continue to pay their respects in future. The $20,000 in federal money would be better spent maintaining existing memorials, they argued.[ix]

In response, those advancing the project wrote of the support they received from all three levels of government, both local and provincial arms of the Royal Canadian Legion, and what they believed to be “the vast majority of our community.” They noted that the “extensive” documentation provided in support of their claim had convinced “top military historians in Canada” as well as the staff of the Community War Memorials Program, and now named a specific veteran (Corporal George Ellwin Champion) as the man whom “evidence” (unspecified) showed to have named the road. The memorial’s rural location and dedication to all Islanders who served (rather than simply those who died in the war) made it both unique and fitting, given the rural roots of most Island soldiers and the focus of other memorials on the fallen, they added.[x] And finally, in a bid to win readers who remained unconvinced, they appealed on more emotional grounds, asking: “Can there be too many ways to remember those who gave so much of themselves?”[xi]

Unimpressed, Lockerby derided such “lofty references to certain out-of-province historians with close military connections, who had probably never heard of Malpeque,” and instead challenged the project’s supporters to “put their evidence before neutral, professional Island historians, such as those at UPEI.”[xii] But this was not simply a case of favouring local experts over those off-Island: Lockerby brandished a 2009 letter from the director of the Department of National Defence’s Directorate of History and Heritage explaining that the evidence in support of the Ploegsteert/Plug Street connection was “insufficient.” Lockerby claimed that the project promoters did an end run around this setback by instead getting the local councillors – who lacked any historical expertise – on board and then using that support to leverage provincial and federal support. He demanded to see the evidence of Corporal Champion having named the road (and deemed the man’s presence in Belgium inadequate), and reiterated an earlier criticism of the plaque’s location, implying that its situation “within a few feet of a potato field” was inappropriate for any war memorial.[xiii]

The claim to local and/or historical authority asserted by Lockerby and his supporters could not, in the end, overcome the combined weight of government support, military authority, and a centenary impulse to commemorate, as wielded by Murray and his camp. The memorial project went ahead.

The new Plug Street signage: street sign and memorial cairn, September 2014.

On 3 August 2014, not far from the main Malpeque intersection and its 93-year-old memorial, the new Plug Street memorial – draped, prior to being revealed, in a large Union Jack flag – was officially unveiled at a small ceremony attended by a variety of government officials and dignitaries. The true memorial remains the road itself, but the site is now marked by a street sign featuring a red poppy logo, and an accompanying stone cairn and plaque.

Text of the Plug Street memorial plaque.

Yet Lockerby managed to get, if not the triumphant last laugh, then at least a quiet, vindicating chuckle: as he pointed out in a post-unveiling letter, the text of the Plug Street plaque not only contained errors in its description of the original Ploegsteert region, but also dedicated most of its space to Plug Street itself and only one line to Islanders who served in the Great War.

Commemorative monuments (in any form) are frequently controversial – at least in their planning and early placement stages – because they claim public space to make statements about the past. The very point of them is to force passersby to confront the messages they convey and to shape the present by means of reminders from the past. Malpeque’s Plug Street controversy clearly echoes debates that began during and immediately following the Great War itself. From the most modest civic cairns and memorial libraries to the grand public monuments in Ottawa, St. John’s, and Vimy, Canadians have argued for a century over the same basic issues: “You want to put what, where?” Nor are form and location the only sticking points. The “message” or “meaning” of a given memorial is frequently at the heart of the debate, even when there is a general consensus around the desire to commemorate. The question is, commemorate what, exactly? Yet historians of public memory (such as those cited earlier) have shown that once the memorial is created, viewers attach their own meanings to it in ways that defy prediction and instead follow the contours of evolving understandings of the past, the needs of the present, and aspirations for the future. (Case in point: a new movement afoot in Russia to raise memorials to bloodthirsty 16th century tsar Ivan the Terrible that speaks to the current nationalist vogue for “strongman” leaders.) A talented sculptor can evoke emotion in successive generations with an impressively heroic or hauntingly bereaved figure, and the text on a plaque can continue to proclaim the accepted truths of one period through those that follow. However, only the viewers themselves determine whether these meanings continue to be taken at face value, or are read ironically, scoffed at, misunderstood, or dismissed.

The commemorative street sign for Plug Street, September 2014.

The recent commemorative conflict in Malpeque, Prince Edward Island, shows that size does not matter: the politics of commemoration are a high stakes game regardless of whether the subject of debate is a local plaque and street sign, or a colossus in a national park. At stake is whose version of the past will be remembered, and how. Yet it is not the players themselves who determine who wins, but generations yet unborn. In this sense, commemoration is the ultimate gamble.

————–

Dr. Sarah Glassford is a social historian of 20th century Canada, currently teaching in the Department of History at the University of Prince Edward Island. She is the author of Mobilizing Mercy: A History of the Canadian Red Cross (MQUP, 2017), and co-editor with Amy Shaw of A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War (UBC Press, 2012).

ActiveHistory.ca is featuring this post as part of “Canada’s First World War: A Centennial Series on ActiveHistory.ca”, a multi-year series of regular posts about the history and centennial of the First World War.

References

[i] Robert Rutherdale, Hometown Horizons: Local Responses to Canada’s Great War (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004); David Macfarlane, The Danger Tree: Memory, War, and the Search for a Family’s Past (Toronto: Macfarlane, Walter & Ross, 1991).

[ii] Jonathan Vance, Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning, and the First World War (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997); Joy Damousi, The Labour of Loss: Mourning, Memory and Wartime Bereavement in Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[iii] “Funding announced for Battles of Ypres monument in Malpeque,” The Guardian, 9 November 2014, www.theguardian.pe.ca.

[iv] Ryan Ross, “Is Plug Street named for Belgium’s Ploegsteert?” The Guardian, 10 March 2014, www.theguardian.pe.ca.

[v] “WWI ‘Plug Street’ memorial has ‘no historical integrity,’” CBC News, 4 August 2014, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/prince-edward-island.

[vi] “Quagmire dedicated?” letter to the editor by Earle Lockerby, The Guardian, 12 August 2014, www.theguardian.pe.ca.

[vii] “PEI’s Route 2 to honour veterans,” The Guardian, 30 October 2011, www.theguardian.pe.ca.

[viii] It is interesting to note that although all three claimed – as Islanders do – this enduring identity rooted in their PEI connection, at the time of writing Werner and MacGougan lived in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia respectively, while Lockerby lived at least part of the time in Ontario.

[ix] “Construction of new Malpeque monument ill-conceived project,” letter to the editor from Garth MacGougan, Earle Lockerby, and Mary MacNutt, The Guardian, 30 November 2013, www.theguardian.pe.ca; “Malpeque already has a war memorial,” letter to the editor from Earle Lockerby, Mary (MacNutt) Werner, and Garth MacGougan, The Journal Pioneer, 4 December 2013, www.journalpioneer.com. The two letters were identical.

[x] Some of the more recent Island memorials (such as the one in Cardigan, PEI) do list all community members who served. The decision to do so irked some locals who considered being stationed in Newfoundland or Halifax during the Second World War insufficient grounds for inclusion on a memorial alongside those who fought and died overseas. My thanks to Islander and PEI historian Dr. Edward MacDonald for sharing his local knowledge on this subject.

[xi] “Monument recognizes sacrifices of our ancestors on battlefields which were very far from home,” letter to the editor from S. Dennis Hopping, J. Darrach Murray, Gilles Painchaud, and Wes Sheridan, The Guardian, 17 May 2014, www.theguardian.pe.ca.

[xii] The University of Prince Edward Island

[xiii] “Despite claims, no historical facts back up cairn decision,” letter to the editor by Earle Lockerby, The Journal Pioneer, 9 June 2014, www.journalpioneer.com.

Your article says that Malpeque (PEI) is located in the northwest corner of Queens county. That is incorrect. Malpeque is located in the northeast corner of Prince county.