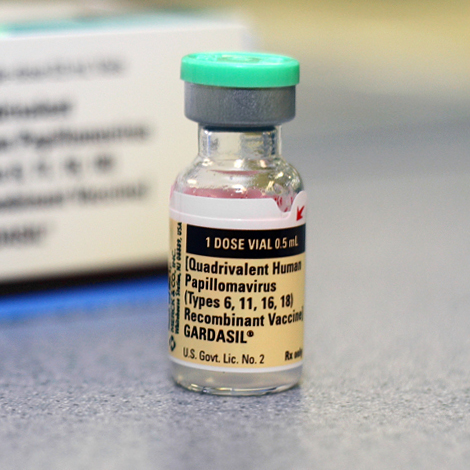

The HPV Vaccine (image courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

By Angela Rooke

For several years now, school boards across the country have been providing the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to girls and young women. But it seems the debate is just getting fired up, especially in Calgary, where the top Catholic Bishop successfully urged many Catholic schools to refuse to administer the vaccine on the grounds that it leads to promiscuity.

In this post, I suggest that the past can shed light on the important question of how a vaccine that prevents cancer could spark a debate about girls’ sexuality, promiscuity and moral values.

Most of us who attended public school as children will have encountered some form of school-administered public health program. I distinctly remember the cart carrying small, free cartons of milk being wheeled into our elementary classroom every day during lunch period. I also remember sweating my way through the head-lice inspections in fifth grade, so very afraid I would be publicly shamed by the nurse who was working her way through my always-tangled, permed hair. I’m sure I’m not alone in remembering these intrusions into the classroom. Public health programs have targeted children through Canadian schools since the late-nineteenth century. Throughout the twentieth century, school children were vaccinated for a variety of different diseases, including polio, meningitis, tetanus, measles, mumps, and rubella. And so, when some provinces began to provide the HPV vaccine to Canadian girls in their schools, this was, really, nothing new. The Canadian government recommended the vaccine for girls between nine and thirteen years of age back in 2007. But the program is not nearly as successful as public health promoters hoped it would be. Recent data from Ontario, where the government provides the vaccine free to eighth graders, suggest that only 55% of Grade 8 girls were vaccinated.

The vaccine, when given to girls and young women between the ages of nine and twenty-six, protects against two types of HPV that account for 75% of cervical cancers. It also protects girls and young women against 70% of vaginal cancer cases and up to 50% of vulvar cancer cases.

But the discussion and debate that surrounds the vaccine centres less on this scientific evidence, or even on concerns over possible side effects, than it does on sexuality. Fred Henry, Catholic Bishop in Calgary, proclaims, ‘”It’s not about a matter of statistics.” He, along with others, attacks the distribution of the vaccine in schools on the grounds that it might promote promiscuity among the country’s girls and young women. The idea is that, by removing some of the risks associated with sexual activity, the vaccine would encourage girls to engage in sex earlier than they otherwise might. In an op-ed to the Calgary Herald just a couple of weeks ago, he “urge[d] all boards to say “no” to the administration of the HPV vaccination program in Catholic school districts.” He argues that the vaccine might do more harm than good:

If we don’t attempt to change sexual behaviour that is responsible for transmission of the HPV, but attempt to solve the problem by getting a series of shots, then we don’t have to exercise self-control, nor develop virtue, but can use medicine to palliate our vices. The technological solution requires no change in behaviour. It does not really address the cause, but masks it, and actually undermines efforts to achieve the most efficient solution. [click here to read the whole letter]

His efforts over the last few years have been quite successful. According to the National Post, only 18.9% of girls in Calgary’s Catholic schools were vaccinated, compared to the nearly 70% of girls in the Edmonton Catholic board.

There is, of course, no evidence that the vaccination leads to promiscuity among girls, however that might be defined. In fact, according to vaccine advocate and Assistant Professor of Community Health Sciences, Juliet Guichon, “What we see anecdotally is that the children don’t jump into bed, they go out for recess.” So the question is: what gives this argument such resonance? The Bishop is certainly not alone in making the debate one about sexuality. In the United States, similar discourse helped to make the HPV vaccine a hot-button issue in the 2011 Republican presidential debates. So, how is it that a cancer vaccine can spark a debate about vice and promiscuity? After all, no one suggests that a tetanus shot might increase kids’ inclination to play with rusty nails in the backyard.

As history shows us, when adults fear the future, or when they are concerned about the changing roles of women, children, and youth, those anxieties are often framed in terms of sexuality. Mary Louise Adams, for example, examines the moral panic over comics in the 1940s and the 1950s. In this Cold War context, it was feared that comics would promote lesbianism among girls (especially those who read Wonder Woman) and homoerotic fantasies among boys: two forms of ‘sexual deviance’ linked in contemporary discourse to communism. Carolyn Strange points out a similar focus on sexuality in turn-of- the-twentieth-century Toronto, when there was a huge influx of young, single women coming to the city to work. Rather than tackle the bigger issues of low wages or adequate housing, reformers decided to focus instead on girls’ sexual lives and issues of immorality. Karen Dubinsky has also zeroed in on the sexual panic over urban girls in this period. The panic centred on strangers, city streets and sexual danger. She shows that, in reality, most sexual assaults against women and girls were perpetrated by people in their own households and families, and that a rural berry patch could be just as dangerous as a downtown street. What this history teaches us is that moral panics usually serve to do one thing: deflect attention away from social realities.

Today, as in the past, discussions of sexual promiscuity, sexual deviance or sexual danger reveal wider concerns about the changing roles of women, children, and youth and they similarly deflect attention away from more serious issues. Ask an adult to describe how young people today are different from those in the past and they are as likely to mention the problems of ‘sexting,’ sexy facebook profile photos, or too-skinny jeans as they are to mention childhood poverty, poor employment prospects, or high levels of student debt. Usually, these discussions about the sexuality of children and young people are also gendered. In the case of the HPV vaccine, the gendered nature of the debate is clear. Had the vaccine been introduced first to boys and young men, I doubt the concerns over promiscuity would have as much currency. More often than not, these debates also ignore evidence that shows declining rates of risky sexual behaviour among teens. A study of American teens shows that, between 1991 and 2001, the percentages of high school students who had ever had sexual intercourse and multiple sex partners decreased, while condom use among those who ever had sex increased over the same period. There’s something about the deployment of sexuality in public discourse that tends to make us lose focus on the evidence and on the issues that matter most.

Women’s history and the history of childhood and youth offer us ways to think critically about how promiscuity, sexuality and morality are used in current debates about children and young women. This critical historical perspective becomes all the more important when we discuss things like HPV, which concerns women’s bodies, women’s health and women’s lives. It is also important because of issues of access. The cost of the HPV vaccine – a steep $400 for the three doses – would prohibit many from ever getting vaccinated outside the school programs. How many young girls will grow up to be women with cancer only because people were concerned they might have sex too young, too much, or in ‘dangerous’ ways?

Angela Rooke is a Ph.D. Candidate at York University who specializes in Canadian history and the history of Gender, Women, and Childhood. Her dissertation examines the history of Sunday Schools and other church-based programmes for children in Ontario between the 1880s and the 1930s.

Great article Angela

Excellent analysis Angela. Can I post a link to this on the HCYG webpage?

Excellent analysis, Angela. Can I post a link to this on the HCYG webpage?

Thanks Tarah and Nancy. Tarah, of course you may post it on HCYG!

Great post! One of the reasons that I am fascinated with the public debate over this issue in Ontario is that because the girls are in grade 8 they can consent to getting the vaccine even if their parents do not (and likewise, they can decline even if their parents request they get it). When I hear people discussing this on talk radio or online or letters to the editors they tend to be outraged that our public schools would allow young women aged 12 or 13 to have autonomy over their own bodies. I find this cultural attitude that young people must not participate in decision-making regarding their own bodies and health (regardless of the position on this vaccine) is much more widespread, and probably harmful, than the questions about morality surrounding this issue.

(http://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=ontario%20hpv%20vaccine%20parental%20consent&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CFkQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.health.gov.on.ca%2Fen%2Fms%2Fhpv%2Fdocs%2Fhpv_parents_faq.pdf&ei=ds8GULyfL-bo6gGagdHOCA&usg=AFQjCNHuzKbz20K32Z6vfOgLbD7qmLc_6A&cad=rja)

Thanks for the comment and the link, Patti. The issue of a girl’s autonomy over her own body is a really important point. It would be great to find out how many health care providers actually do allow the child to get the vaccine against their parents’ wishes, since it sounds like it is left up to the nurse/doctor’s discretion.

An interesting article was posted this afternoon that speaks to Patti’s comment above. According to the article, The University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital did a national poll asking adults about allowing adolescents age 12 to 17 years old to receive the HPV vaccinations without parental consent. Only 45 percent of those polled would support state laws allowing the HPV vaccination without parental consent.

The moral/ethical concern was evident. “Those who did not support dropping parental consent were asked about their reasons. The most common reason, cited by 86 percent, was that HPV should be a parent’s decision; 43 percent cited the risk of side effects of the vaccine. About 40 percent said they have moral or ethical concerns about the vaccine.”

Perhaps more interesting was that there was much more support for the idea of allowing girls to get treatment for other kinds of sexually-transmitted infections without parental consent. “The majority of adults view HPV vaccination as distinct from sexually transmitted infection prevention.”

Why the difference? Is it that, unlike HPV, most other treatments for STIs come after girls have already been sexually active? So, ultimately, it boils down to the concern that the HPV vaccine, which is most effective when given to girls before they become sexually active, might lead to ‘promiscuity.’

Read the whole article here: http://www.marketwatch.com/story/parental-consent-for-hpv-vaccine-should-not-be-waived-poll-says-2012-07-18

Excellent article, Angela! As someone who is looking at the history of medicine in a much earlier time period (fourteenth- and fifteenth-century England), I find this modern discourse on female sexuality and reproductive health eerily familiar. Management of the sexual and reproductive capacities of the female body was – and continued to be – an organizing principle in patriarchal cultures. From the censoring of any mention of contraception, abortifacients, and even emmenagogues in medical literature directed to female audiences to the prosecution and persecution of healers who offered such remedies to their patients, the dominant religious and medical discourses in this period stressed the need for women to “exercise self-control” in order to “develop virtue”. When I read Henry’s phrase, “use of medicine to palliate our vices,” I thought, for a moment, I was skimming a leechbook written by a medieval cleric.

Thanks for the early-modern perspective, Ashlee! My historical examples draw on the period I study, but thanks for reminding us that the HPV vaccine discourse draws on a much older tradition, and is by no means limited to North America. For anyone interested in the themes Ashlee mentions, I can recommend reading Wendy Mitchinson’s work on 19th Century Canada; she, too, looks at obstetrics, abortion, contraception and the like, and highlights many of the same issues. I will leave it to Ashlee to recommend (and write!) articles and books on the early modern period outside Canada.

Hi Patti,

Just read your comment about Ontario and was wondering if you could say more about why girls can consent to it on their own if parents say no. Is this becuase of their age? Legal age of consent? Could you direct me to where I might find this information?

Thank you,

Katelin

Excellent work done, really very informative post. Thanks for sharing. You bring the great points HPV Vaccine Controversy and I must say so helpful. you give the advise and awaring people free of cost. Such a nice thought Wonderful. Keep it up. J