Hannah Roth Cooley

Over roughly the last decade, settler Canadians and Americans have started to take note of Indigenous activist initiatives, thanks in large part to social media.

Beginning with the explosion of #IdleNoMore in 2012, social media has become an important tool for circulating political messages and sharing cultural knowledge within and beyond Indigenous communities.

Certainly, Indigenous Peoples advocating for their inherent rights and sovereignty is not new; despite British, American, and Canadian efforts to assimilate Indigenous Peoples into North American colonial societies and undermine their nationhood, generations of activists have pushed for recognition of their political rights, adherence to treaties, and respect of their land rights.

But what was new in 2012 was the use of social media to share these messages and build a media community. Or was it?

While social media certainly provide these opportunities, so too do more traditional media, including newspapers. And Indigenous-led organizations took up newspaper printing long before Facebook was even a glimmer in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye. As early as 1828, with the founding of the Cherokee Phoenix, Indigenous nations undertook newspaper publishing as a means to spread information about events affecting their communities and to connect with other interested readers, near and far.

The capacity of newspapers to connect people has always been particularly interesting to me. As a scholar of Indigenous journalism, I find myself drawn to moments when we can see the interactions between a newspaper’s creators and its readers, who co-create their own community around the publication.

One of my favourite examples that shows the connecting power of community journalism is the Kainai News, a newspaper published by the Kainai (or Blood) nation in southern Alberta. Beginning in 1968 until the early 1990s, Kainai News published a mix of hard news, editorials, and reader contributions to create what was called (at least by the paper’s own producers) “Canada’s Leading Indian Newspaper.”

Reading this newspaper’s early issues, from the late 1960s and early 1970s, as I did for my PhD dissertation, shows us the power of community produced media for bringing people together. This was particularly significant in the case of members of the Siksikaitsitapi, or Blackfoot Confederacy, whose territory spans the region currently covered by the Canadian province of Alberta and the American state of Montana. When the border was drawn in the nineteenth century, American and Canadian officials sought to demarcate members of the Confederacy who would be “American” and those who would be “Canadian,” ignoring the existing community structures, relationships, and geographies of these nations.

But Kainai News shows us that colonial efforts to divide people never worked quite as intended; roughly a century after the imposition of the border and treaty signings with Canadian and American governments, Siksikaitsitapi continued to seek out connections with their relatives across the border. In 1974, Kainai News hired reporter Peaches Tailfeathers to write a regular column titled “Across the Line,” relaying stories from American Blackfeet territory to readers in southern Alberta. That same year, the publisher of Kainai News, Indian News Media, amended its bylaws to explicitly include Blackfeet in Montana as part of their audience. They further extended membership rights in their organization to Blackfeet in Montana – previously only Indigenous people living in Alberta had this option. The newspaper clearly recognized the importance of reinforcing the community connections that predated the imposed border.[1]

Kainai News also showed in its pages its relationships with other publications.

Throughout the early 1970s, the editors included in the newspaper requests that they received from other papers to republish Kainai News articles. Additionally, they published requests from small newspapers who wanted to exchange copies or be put on each other’s subscription lists (see map). Clearly, Kainai News served as a model for other Indigenous-led publications. But they also sought to encourage these connections—printing these requests suggests that they were proud of the connections they were making and thought it was important for the readers to know of this growing network of Indigenous periodicals. The Browning Sentinel, based out of Browning, Montana, explicitly encouraged its subscribers to read Kainai News and noted it “compares to the New York Times in their editorials, news items, and photographs.”[2]

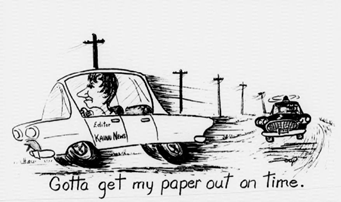

Kainai News was also particularly well-known in the 1970s for the work of its in-house cartoonist, Everett Soop. Soop’s cartoons were sharply witty, sometimes self-deprecating, and often brought forward significant political concerns with levity. His cartoons featured prominent leaders, such as Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who received significant attention in the Indigenous press for his government’s disastrous White Paper policy in 1969.

Soop also used cartoons to poke fun at the newspaper staff itself, making the readers feel like they were part of the creative team behind the paper as well. Soop’s talents were certainly recognized in his own era, with other publications contracting him to draw cartoons for their papers. And Soop continues to be recognized for his artistic and political contributions even decades after he stopped working for Kainai News; a documentary and an art exhibition have been produced focused on his life, work, and activism. Many of his cartoons are also held digitally at Library and Archives Canada, making them a great source for future historical research and writing.

The case of the Kainai News highlights how media could be tools to support Indigenous sovereignty, cultural conversations, and community connectivity long before the advent of social media.

This newspaper published diverse news stories from across Siksikaitsitapi territory and beyond, bringing people together over shared news content and satirical cartoons. The publication provides a rich treasure trove of commentary about major political issues for Indigenous Peoples in North America but was not solely focused on serious and sombre political conversations. This is not to say it was not a political publication, however; its focus on Indigenous community life, success, and humour made it a significant tool in combatting the types of media racism we still see today.

Kainai News, and other publications like it, thus provide important historical sources that deserve greater attention. Their pages provide rich and thought-provoking analysis of the important issues of the moment, and are excellent sources to work with for both teachers and students of history.

Hannah Roth Cooley is an independent scholar who recently completed a PhD in the Department of History at the University of Toronto.

This post is part of an activehistory.ca series on media and history in Canada. Media have been both remarkably important and intensely theorized but also historically understudied. We hope this series highlights the diversity of ways the study of media history informs and contributes to our knowledge of the past and our understanding of the role of media in the present. The editors encourage other submissions on topics related to media history, conceived of broadly. If you are interested in contributing or even just finding out more about this series, please feel free to write to Andrew Nurse at anurse@mta.ca, Hannah Cooley at hannah.cooley@mail.utoronto.ca, or Christine Cooling at ccools@yorku.ca.

[1] “Proposed Amendments to Constitution, Executive Director to All Members of the Indian News Media, May 22, 1974”; Alberta Native Communications; General (1971-1973), box 2; Provincial Archives of Alberta.

[2] “Sentinel Editorial Reprinted,” Browning Sentinel, June 1970, 4.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Blog posts published before October 28, 2018 are licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License.