Aidan Hughes

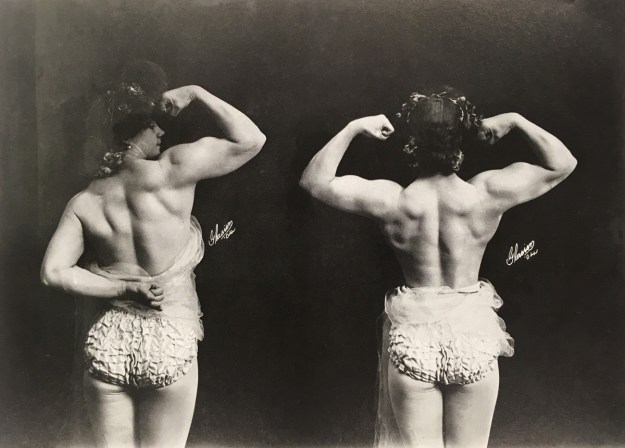

Casual fans of bodybuilding’s breakout docu-drama starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Pumping Iron (1977), may not be aware of its mildly anticipated sequel. In 1985, filmmakers George Butler and Charles Gaines produced Pumping Iron II: The Women. It followed women bodybuilders at a bodybuilding show in Las Vegas during 1983, but mainly focused on two vastly different competitors to explore the expressions and understandings of femininity in the masculine-coded sport. Rachel McLish, the reigning Ms. Olympia champion, performed a socially accepted version of bodily femininity in the film; she was very lightly muscled with some body fat that contoured her body. On the other end of the film’s gender continuum was Bev Francis, a powerlifter-turned-bodybuilder who carried more muscle mass than female bodybuilding had ever seen.

Gender subversion was embodied in Bev Francis. Francis was far more muscular than the other competitors, and the film used her subversive body to drive the plot forward.[1] Conversations between competitors, judges, and onlookers were often in reference to Francis’ body; it is unlikely that femininity would have been as intensely debated had Francis not been a competitor.[2] She challenged women’s bodybuilding so much so that the judges and officials called an emergency meeting to discuss the competition’s ruleset after seeing Francis’ body. Ben Weider – who was second to his brother Joe Weider as the most powerful person in the sport and business of bodybuilding and co-founder of the International Federation of Bodybuilders (IFBB), the premier professional bodybuilding organization – stated “We hope that this evening we can clear up the definite meaning… of the word femininity and what you have to look for. This is an official IFBB analysis of the meaning of the word.”[3] Meditating – and maybe even fantasizing a little – on what kind of woman he wanted to see on stage, Weider explained “what we’re looking for is something that’s right down the middle. A woman that has a certain amount of aesthetic femininity, but yet has that muscle tone to show that she is an athlete.”[4]

By “aesthetic femininity,” Weider was likely referring to Western ideals of thinness and by extension normative attractiveness; the subtext here is that he wanted the bodybuilders to be sexually attractive.[5] This undercut the core objective of a bodybuilding competition – the accrual and presentation of maximal muscle mass and symmetry – while proposing a two-tiered judging standard that segregated men and women in the sport.[6] Nonetheless, this definition is illustrative; femininity in bodybuilding meant having an attractive and thin body, not a muscular one. Muscles were only accepted on female bodybuilders to the degree that they did not obscure normative gender expectations. Weider explained that defining femininity according to prevailing gender norms was necessary “to protect the majority [of less muscled competitors] and [to] protect our sport.”[7] He continued, stating unless “the majority of the girls…say, ‘hey, let’s go for these big, grotesque muscles,” traditional bodily femininity was to be the standard judging practice.[8] Weider’s chauvinistic reference to “grotesque muscles” certainly reveals these men’s thoughts and expectations of women bodybuilders. Weider didn’t leave much to be imagined vis a vis his thoughts of women: “we want people to be turned on, not turned off… women are women, and men are men, and there is a difference, and thank God for that difference. That’s all I have to say.”[9]

Throughout Pumping Iron II, filmmakers Butler and Gaines positioned Francis and McLish as existing on opposite ends of the gender continuum. This plot point materialized itself most visually during the documentary’s finale: the competition. In the pre-judging phase, the judges instructed McLish and Francis to pose beside each other to compare their physiques, and fellow competitor Carla Dunlap was shown laughing at this extreme juxtaposition.[10] Despite their physical proximity, the two physiques were worlds apart. McLish embodied the “aesthetic femininity” that the judges spoke of: she was lightly muscled, had stylized hair and makeup, posed effeminately, and was wearing a bikini with padded breasts at this point of the competition.[11] Francis had “the muscle tone to show that she is an athlete” and then some; she had capped deltoids and bursting pectorals that bulldozed the vision of femininity that Ben Weider and the judges bumbled to defined.[12]

The sole woman judge decided “[i]t would be a total disaster and the sport would go in total reverse [if Francis won]…Bev Francis does not look like a woman. She does not represent what women want to look like.”[13] Francis’ supposed subversion was punished yet again – and this time more severely – when the judges gave her eighth place, despite her being the most physically developed bodybuilder on stage.[14] In doing so, the judges “protect[ed] the majority” who did not have “grotesque muscles,” underlining the presumed problem with Francis’ body that the documentary had made clear.[15]

Rachel McLish embodied the performative acts of femininity in Pumping Iron II; more or less, she was Francis’ foil. Aside from the way she cast herself in the competition, the documentary underlined McLish’s femininity. From the film’s onset, McLish is positioned in diametric opposition to Francis’s gender identity, and she reinforced this in her dialogue. McLish asked Francis “what is bodybuilding to you?” and before letting Francis answer, McLish interjected: “When I’m on stage I want every woman to just want to look like me, or try to achieve what I’ve done: have a perfect body.”[16] McLish went further, explaining “I visualize characters from comic books with tiny little waists and perfect legs with little muscles, like Wonder Woman.”[17] This is similar to how male bodybuilders in the 1980s performed gender through “comic-book masculinity” according to ethnographer Alan Klein.[18] With the inverse fear of appearing “manly,” McLish modelled herself after fictional women with exaggerated feminine qualities to emphasize her own femininity. In the context of male-dominated bodybuilding, McLish’s “comic-book femininity” should be understood as a performative act that she strategically used to stabilize her own gender identity in a sport invariably coded as masculine.

While the majority of Pumping Iron II focused on the contrast between Francis and McLish’s gender performances, the other competitors’ definitions and representations of gender were less absolute and more nuanced. Accounts from the film’s sub-characters offer an opportunity to explore how femininity may be redefined through bodybuilding, rather than simply performed or subverted. However, the directorial choices made by Butler and Gaines in filming the sub-characters obscured their definitions of themselves. Whether knowingly or unknowingly, the filmmaking process undercut the bodybuilders’ complex definitions of femininity by filming their conversations against sexualized backdrops. This was most overt in the shower scene where their naked bodies were only scantly concealed by suds, but also subtly in a hot tub scene.[19] By sexualizing these competitors, Butler and Gaines overlooked the depth of these conversations and misinterpreted them to mean that the women were only using their muscled bodies to cast themselves as sexy. In overlaying these conversations with sexualized images of the women, Butler and Gaines more or less doubled-down on normative expectations of women: the purpose of the female body was to be attractive to male viewership.

Certainly, Pumping Iron II tells us much about how far women’s bodybuilding has come: a slew of regulatory reforms between 2000 and 2020 opened several categories for women of different musculature (wellness, bikini, fitness, physique, and bodybuilding divisions). While these divisions didn’t mark the end of the blatant sexism we saw in Pumping Iron II, it is indeed progress. But the film is also instructive of how gender has been (and continues to be) mobilized in sport to subjugate athletes who fail to meet the ideal. At a time when trans children are being excluded from sport and grown men are hurling sex toys onto the WNBA court, I’m reminded of Ben Weider’s desire to “protect” bodybuilding from people like Bev Francis, whose body he found confusing, offensive, and impossible to sexualize. The toxicity we are witnessing today has very little to do with sport, fairness, or ability; it’s about rearticulating hegemonic notions of masculinity and femininity at a time of great gender instability. Women’s bodybuilding, existing at an awkward intersection of sport and gender, can tell us much about these anxieties.

[1] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[2] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[3] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[4] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[5] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[6] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[7] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[8] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[9] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[10] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[11] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[12] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[13] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[14] Butler, Gender Trouble, 178.

[15] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[16] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[17] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

[18] Alan Klein, Little Big Men: Bodybuilding Subculture and Gender Construction (New York: State New York University Press, 1993), 267.

[19] Butler and Gaines, Pumping Iron II.

Aidan Hughes is a PhD student at the University of Guelph. He studies steroids and bodybuilding culture.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Blog posts published before October 28, 2018 are licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License.