By Evan J. Habkirk and Janice Forsyth

In March 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada completed its six-year investigation into the experiences of Indian residential school students who had survived years of neglect, abuse, and trauma at these institutions. More than 6,000 witnesses testified at hearings held throughout the country. The purpose of the Commission was to collect and document the history of these schools from the perspectives of former students, bringing a voice to a group of people whose issues and concerns had long been neglected by the federal government and religious organizations, the two main institutions responsible for the establishment and maintenance of the schools. The 527-page Executive Summary was clear in its aim to help Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians move forward from a traumatic past by starting another, somewhat different, conversation: “Now that we know about residential schools and their legacies, what do we do about it?”[1]

From our perspective, as researchers who study the physically active body at Indian residential schools, the Executive Summary brought much needed attention to sport and recreation as important elements of the residential school experience, as well as the reconciliation process. Indeed, sport and recreation are discussed in three distinct sections of the Summary: “Sports and culture: It was a relief”; “Public memory: Dialogue, the arts, and commemoration”; and “Sport: Inspiring lives, healthy communities.” Each section makes it clear that attempts to address the legacies of the school system must include detailed examinations of the different types of sport and recreation opportunities that were provided at specific institutions, as well as how former students understood those opportunities. It was exciting to see an official document acknowledge the significance of this part of Indian residential school history – a history that has affected the lives of so many, across multiple generations.

But having said this, we also found the discussion somewhat inadequate. Our concern stems primarily from the lack of a theoretical approach to understanding the role of physical activity culture in the residential school system. Statements in the Executive Summary, such as sports “helped them make it through residential school”[2] or “[sport] made their lives more bearable and gave them a sense of identity, accomplishment, and pride,”[3] while certainly true, glosses over the distinct and diverse ways to understand the role and significance of physical activities in these schools. We wonder, for instance, to what extent did school officials, including instructors, missionaries, and government agents, use physical activities to exploit the students for social, political, and economic gain? And how did the students transform the meanings that were attached to these activities to “make it through” these highly oppressive environments, especially since many of the activities were intended to eradicate and replace traditional Aboriginal values and practices?

This problem is not limited to discussions about the Indian residential school system. Much of our current reporting on sport encourages this uncritical view, as do most sports awards and commemoration projects, like the many halls of fame that acknowledge the achievements and contributions of individuals and teams. However, in adopting such a narrow view, we fail to notice how the physically active body is invested with meaning, and, moreover, that this investment process is neither innocent nor arbitrary. Rather, the physically active body is a highly contested site that power relations are inscribed into, and where they are also reinforced or challenged. It is more productive to see and understand the moving body as a politically charged object that takes on different meanings in different historical contexts.

Critically Engaging with Sport and Residential Schools

Different theories and concepts can be used to understand how power relations work on and through the body. Throughout this discussion, for instance, we make use of Michel Foucault’s concept of “normalization” to interpret how and why moving bodies are classified as either normal or deviant, or some variant in between. These socially constructed standards of how bodies ought to move render the body knowable and controllable. Such power relations can have very real effects, with far-reaching implications for individuals and groups who seek to understand their identity or secure cultural survival through physical culture, even if the individuals and groups do not immediately perceive the effects in that way.

Consider a few examples of how politics are inscribed through the moving body, specifically, the prohibitions against the Potlatch and Sun Dance ceremonies, and the Tamanawas dance, which were vital cultural practices for Aboriginal people living on the Plains and along the Pacific North-West coast. Forced changes to those practices would dramatically alter their entire ways of life, from gender relations, to economic transactions and exchange networks, to spirituality.[4] Whether or not colonial administrators immediately grasped the significance of those ceremonies to Aboriginal cultural survival is open to question. However, fundamental changes were precisely what colonial officials endeavoured to achieve in their efforts to assimilate Aboriginal people and displace them from their lands. Beginning in the 1880s, missionaries and government officials viewed the potlatch and sun dance as deviant bodily practices, and attempted to replace them with behaviours understood to be more civilized and productive, using Euro-Canadian sports and games to impose such re-definitions on Aboriginal people.[5] Sports day celebrations became a popular feature on many reserves across Canada, with intra- and intercommunity competitions being encouraged by Indian agents and federal policy makers alike.[6] Some Aboriginal groups carried on their cultural traditions either in secret, as a private exercise, or within a framework that positioned their traditional practices more as entertainment than ceremonies that were vital to their overall well-being.[7]

Issues concerning normalization and power relations are even more obvious in the residential school system, where agents of the church and state had nearly unrestricted access to thousands of Aboriginal boys and girls, whose bodies were regulated and controlled through seemingly mundane practices such as military drill, calisthenics, as well as sports and recreation. These practices were designed not to instill Aboriginal pride among the students, but rather, to break down their cultural ties and identities by cultivating a new sense of self-awareness structured by Euro-Canadian ideas about how the body should be used, thus producing the taken-for-granted understanding that the properly trained body was that which served dominant economic and military interests, and not traditional Aboriginal ways of living.[8]

Mohawk Chapel Confirmation – 1918 – Private Collection

Military drill exercises as methods of physical instruction are a case in point. Although these exercises were never explicitly part of the residential curriculum, they were a common feature of the school system from the late 1800s well into the 1950s.[9] Their prevalence and persistence speak to their importance in the residential school experience of many students, especially the boys, for whom these activities became a regular part of their daily routine. Though one could argue that a military structure was needed in order to house, clothe, feed, teach, and control a large number of children, and that military drill was a way to promote health among the students, the rigid structure served a deeper disciplinary function. Continual drilling and military appearance taught the children how to follow orders; how to live a regimented life structured by the clock; how to obey their superiors and respect the established hierarchy, including the junior ranking officers who were put in place to police the other students; and how to regulate their bodies through the rehearsal of prescribed movements. In other words, military drill served to instill in the students a deep appreciation for what constituted proper body movement in service to the state.[10]

Far beyond merely reconstituting individual identities, the use of military drill in residential schools also transmitted important symbolic messages to Canadians generally. Often, students were made to perform military exercises in front of citizens in neighbouring towns and cities. The live staging of young Aboriginal bodies carrying out recognizable movements served as visible proof that Aboriginal youth, if separated from the influence of their family and community and subjected to proper instruction, could be turned into productive members of society. The underlying message was that residential schools were places that provided positive, structured transformation for Aboriginal youth, thereby helping them to assimilate into the dominant culture by learning how to contribute to state priorities.[11] Thus, the military drill, as a form of public spectacle, provided a visible framework for understanding the potential for Aboriginal assimilation in Canada and helped to justify the ongoing development and maintenance of the school system.

Such was the case at the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario, where Rev. Robert Aston introduced military training in 1872 to create the order and discipline he felt was lacking among the students. Although a government sectioned cadet corps was not formed until 1909, Ashton broke the students into squads led by sergeants and corporals, introduced good conduct badges, black lists, a solitary confinement cell for those who misbehaved, and trained them to line up and march to the dining room, class room, chapel, and other places on the institution’s grounds.[12] He would also establish a parade square on the school grounds where the children would line up and number themselves off before going about their daily chores. By 1894, the boys were made to wear grey uniforms tailored by the girls, with polished boots, and performed drill exercises under the name of the Mohawk Institute Cadets.

The Mohawk Institute Cadets soon developed into a popular spectacle, with the public being invited onto the school grounds to watch the students perform. Even members of the Royal family witnessed Rev. Ashton’s civilizing efforts. The Cadets were also frequently taken outside the school grounds and paraded through the city of Brantford. In 1896, they participated in the Brantford Gala Day Cadet Competition where they beat the Brantford Collegiate Institute Cadets, the premier cadet corps comprised of upper and middle class children from Brantford. The victory was a significant achievement for Ashton, in that it demonstrated that his civilizing efforts were successful. After Ashton’s retirement in 1903, his son A. Nelles Ashton carried on these demonstrations. Taking over the school, the younger Ashton established the #161 Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps, participating and taking first place in the No. 2 Central Ontario Military District rifle competition.[13]

Mohawk Institute Cadet Trophy 1896, Author’s Photo

The Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps was disbanded in the 1920s,[14] but other Canadian residential schools retained this practice as an efficient and cost-effective way to promote their civilizing efforts. Beginning in 1933, the Cecilia Jeffery Residential School in Kenora, Ontario, sent their cadet corps on a performance tour of Ontario, Manitoba, and the United States. They performed mostly for the general public, and the press reported positively on their performances, focusing on the novelty of the Aboriginal cadet band. In 1934, performance requests for the Cecilia Jeffery Band began to be sent by non-Aboriginal groups, including requests to play at the King’s coronation in England in 1937, at the Glasgow World’s Exhibition in 1938, and for the King and Queen’s visit to Winnipeg in 1939. While Ottawa funded some trips, it did not support the requests to perform in England or Glasgow. The Minister for the Department of Mines and Resources, who was responsible for Indian Affairs, explained that while funding for the overseas trips were denied, “every encouragement should be given to this Band to visit other places in Canada or the United States.”[15] Following the Minister’s advice, the band continued to tour Ontario, Manitoba and the United States until 1939, promoting the civilizing work being done through the residential school system.[16]

Beyond Binaries of Positive and Negative

A related problem is posed by the way in which sport and recreation are framed in the Executive Summary as positive elements of the residential school system. It states that sporting accomplishments made student lives “more bearable and gave them a sense of identity,”[17] then calls for “public education that tells the national story of Aboriginal athletes in history.”[18] This positive framing is supported by autobiographies of former students, who frequently describe sport and recreation as the only good thing that happened at the schools. Basil Johnston’s Indian School Days, wherein sport occupies as large part of the storyline, is a representative example. Johnston, who attended Spanish Indian Residential School in Northern Ontario in the late 1930s and 1940s, explained that his purpose in writing the book was “to recount and relive some of the few cheerful moments in an otherwise dismal existence, a memorial to the dispossession of my people, the Anishinauback, to find or to create levity even in the darkest moments.”[19]

It is not hard to see why sport and recreation are viewed as positive elements of the residential school system. The entire institution was intended to strip Aboriginal children and youth of their cultural identities, using violence and repression as their main instruments for inculcation. Yet, framing sport and recreation as “good” components of the system implies that there were some beneficial elements to the broader program of assimilation that negated some of the “bad” things that schooling did. While we recognize that some people generated positive meanings about their experiences at school, the binary limits our ability as researchers to see the complex history of struggle that took place among the young at these institutions, and instead channels our attention into an itemized listing of bad/negative versus good/positive elements.[20]

The inadequacies of adopting a positive/negative view become clearer when sport is framed within the larger context of the residential school system. When Indian Affairs began promoting these activities in the 1940s, they were encouraged as a form of health promotion to counter the diseases rampant in the schools. By 1949, when the government began to wind down the residential school system, competitive sports came to be seen as a way to integrate Aboriginal students into the broader public school system. Images of Aboriginal youth playing in friendly competition with other children would go a long way in convincing mainstream school officials, and the voting public, that Aboriginal youth should be allowed into the provincial school system. To aid its agenda, Indian Affairs created a new portfolio for Physical Education and Recreation within its branch in 1949.[21]

One of the few residential schools to establish a competitive team at this time was the Sioux Lookout Indian Residential School, located in northern Ontario. The Anglican Church, which helped to establish the institution in 1926, had a clear vision of how organized activities would contribute to its broader mission:

Unlike their playmates of civilization, the Indian children’s recreation must be cultivated and developed, as they lack the knowledge of creating their own amusements. Strange as it may seem, the average Indian cannot swim, so that their recreation becomes an education. Once taught, they become keen, and display good sportsmanship and courage.[22]

Students playing hockey at school, Circa. 1951, “Pelican Lake Indian Residential School: Photo Album,” File. no. 130, Shelf location 2010-007-001, Algoma University Archives

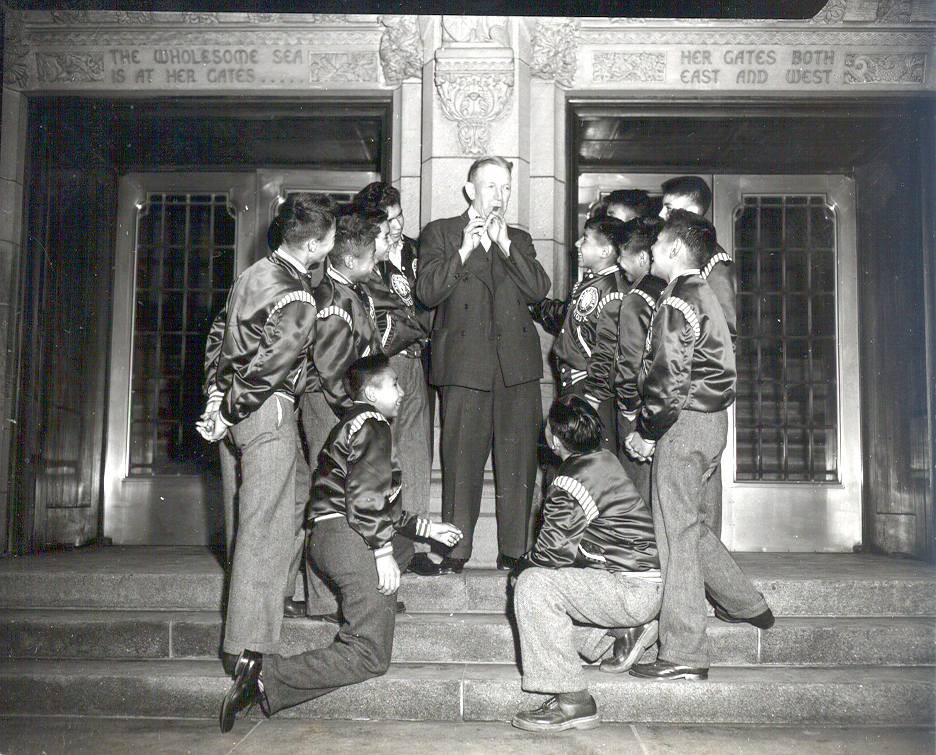

School officials, with support from residents of the town of Sioux Lookout, developed the Black Hawks, a ten-member hockey team whose players were aged 12 to 14. The children had been taught how to skate and stick handle by 1948, began competing locally in 1949, and by 1950, they had amassed an impressive record of 17 wins and 1 loss, capturing the Sioux Lookout bantam title as well as the Thunder Bay district crown.[23]

In April 1951, Indian Affairs and other non-First Nations organizers from Sioux Lookout arranged a public tour for the Black Hawks to play non-First Nations teams in Ottawa and Toronto. The tour consisted of three games: two at the Auditorium in Ottawa and one at the Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. Two principal reasons were cited for this trip. The first, espoused by the supporters and organizers from Sioux Lookout, was to reward the Black Hawks for their “ability, behavior and sportsmanship” on the ice.[24] The other purpose, espoused by Indian Affairs, was to “encourage hockey” among Aboriginal people,[25] a rather dubious claim considering the games were hosted in major Canadian cities and not in First Nations communities, and the fact this team, made up of Aboriginal children, were traveling to play teams of non-Aboriginal children.

“Hockey – Sioux Lookout Black Hawks,” Jan Eisenhardt Archives, Western University

The Black Hawks’ games were transformed into highly publicized events featuring some of the highest-ranking dignitaries and hockey personalities that the organizers could muster. One of the games in Ottawa was attended by the Governor General, Lord Alexander, whose son Shane dropped the puck to start the event. Also in attendance were Paul Martin, Minister for Health and Welfare, and Walter Harris, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration. Two Members of Parliament and former NHL greats, Lionel Conacher and Wilfred McDonald, refereed the evening game, where more than 1000 people were in attendance.[26] The exhibition was much more than a sporting competition; it confirmed that under the proper conditions and with careful training, residential school students could be assimilated into the public school system.[27]

“Hockey – Sioux Lookout Black Hawks,” Jan Eisenhardt Archives, Western University

“Hockey – Sioux Lookout Black Hawks,” Jan Eisenhardt Archives, Western University

After five days of traveling and competing, the students returned to the stark contrast of their daily routines at school. The federal government never sponsored another tour for the Black Hawks. Instead, they were left to compete in a small regional league, occasionally playing against non-Aboriginal teams before large-paying crowds in the Sioux Lookout area.[28] The federal government and religious institutions had used the space of sport to highlight their educational objectives and to suppress the damaging effects the chronically underfunded system was having on the youth. While the government and churches publicized their preferred images of the benefits of schooling, the reality of such events for the students was very different. Behind the rhetoric of citizenship, belonging, camaraderie, and acceptance these images supported, residential school sports helped to mask the power relations that continued to structure Aboriginal lives in Canada, including the space of sport. Many former Black Hawks would go on to establish the Little Native Hockey League, an all-Aboriginal league for Aboriginal youth in Ontario that has adapted the ideas of education, citizenship, and sportsmanship to fit their own cultural agendas, rather than that of the church and state.[29] It is just one example of how Aboriginal people have used sport to creatively adapt the colonial forces that sought to eradicate their cultures – an important nuance that would be lost in a binary framework.

Concluding Thoughts

Theories are important because they help us to make sense of the world around us, including the past and its relationship to the present. Viewing the body as a cultural text on and through which meanings can be inscribed, and understanding sport and recreation as critical sites for identity formation, carries far more potential for understanding what happened within these schools than understanding these practices as a binary. Adopting a positive/negative view of the world reduces our ability to make sense of history because it obscures the complex realities of what happened at these schools. This does not mean that we can discount what students say about their experiences. On the contrary, we need to understand their experiences within the broader context of the school system and that of Indian Affairs and the missionary societies, anchoring the students’ stories within the broader record of empire building and capital accumulation. In point of fact, an overly simplistic view of the world goes against the very heart of what the reconciliation process is supposed to be about: creating a new language and understanding of what it means to be Aboriginal in Canada and restructuring the relationship so that Aboriginal people have a valued place in Canadian society as well as a strong voice that can articulate what that valued place looks like.[30]

If we accept the basic premise on which the Commission was founded, that greater understanding is a key to ‘healing’ from the past, then examining all aspects of the residential school system and raising challenging questions about the patterns that emerge from the evidence will be vital to our success. The point here is not to argue about whether sports and games were ‘good’ or ‘bad’ features of the residential school curricula, or to define the outcomes in positive or negative terms, but to examine how these activities played a central role in the program of assimilation, and how students responded to these activities in productive and creative ways, building their ingenuity and resilience one game at a time. This perspective is perhaps more aligned with the ‘truth’ of what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had in mind.

Evan J. Habkirk is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at Western University. His research interests include Indigenous and colonial military history from 1812-1930, the history of Canadian Indian residential schools and Indigenous education, and British imperial policy.

Janice Forsyth is an Associate Professor in Kinesiology, in the Faculty of Health Sciences, and former Director of the International Centre for Olympic Studies at Western University in London, Ontario. She specializes in Canadian and Olympic sport history, and has a specific interest in Aboriginal people and sport in Canada.

[1] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, “Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada,” July 2015, vi. (accessed November 14, 2015). A good starting point for academics considering this question is Thomas Peace, “Truth and Reconciliation While Teaching Canadian History?,” ActiveHistory.ca, November 23, 2015. (accessed November 26, 2015).

[2] Ibid, 110.

[3] Ibid, 297.

[4] Katherine Pettipas, Severing the Ties that Bind: Government Repression of Indigenous Religious Ceremonies on the Prairies. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 1994.

[5] The Indian Act was amended in 1884 to prohibit the Potlatch ceremony and the Tamanawas dance. Further amendments to the Indian Act were made through the years, increasing government control over Aboriginal cultural practices. For instance, the thirst dances (also known as the Sun Dances) were outlawed in 1895. For a general treatment of this subject, see Olive Dickason, Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from the Earliest Times, 4th ed. (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2009), 254-255, 297-298, 301. A summary of amendments to the Indian Act that prohibited these festivals and dances can be found in Christine O’Bonsawin, “Spectacles, Policy, and Social Memory: Images of Canadian Indians at World’s Fairs and Olympic Games,” (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, 2006), 346-349.

[6] Vicky Paraschak, “‘Reasonable Amusements’: Connecting the Strands of Physical Culture in Native Lives,” Sport History Review, Vol. 28, No. 1 (1998): 121-131.

[7] Courtney Mason, Spirits of the Rockies: Reasserting an Indigenous Presence in Banff National Park (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto, 2014).

[8] Janice Forsyth, “Bodies of Meaning: Sports and Games at Canadian Residential Schools,” in Janice Forsyth and Audrey Giles, eds., Aboriginal Peoples and Sport in Canada: Historical Foundations and Contemporary Issues (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2013), 15-34.

[9] Igor Egorov, “General History of Cadet Corps in Indian Residential Schools, 1879-1996,” General Synod Archives of the Anglican Church of Canada, 21.

[10] Some information about the Mohawk Institute Cadets was reproduced with permission from the author’s work with the Great War Centenary Association Brantford, Brant County, Six Nations. See Evan J. Habkirk, “The Cadet Movement” Great War Centenary Association Brantford, Brant County, Six Nations, 10 November 2014. .

[11] J.R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000).

[12] Elizabeth Graham, The Mush Hole: Life at Two Indian Residential Schools (Waterloo, Ontario: Heffle Publishing, 1997), 9, 23, and 40.

[13] Ibid, 106.

[14] The Brantford Expositor, June 1925 and “#161 Cadet Corps” Army Cadet History, (accessed 11 December 2015). The corps was reestablished in the 1940s and then disbanded in the 1970s. Igor Egorov, “General History of Cadet Corps in Indian Residential Schools, 1879-1996,” General Synod Archives of the Anglican Church of Canada.

[15] Letter, A.A. Hoey to Frank Edwards 6 May 1938, RG10, Vol. 8788, File 487/25-10-014 pt.1, LAC.

[16] For more information on how the cadet corps affected First Nations communities in Western Canada, see Jordan Robert Koch, “Îyacisitayin Newoskan Simakanîsîkanisak: ‘The (Re)Making of the Hobbema Community Cadet Corps Program’” (Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta, 2015).

[17] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 297.

[18] Ibid, 298 and 336.

[19] Basil Johnston in Sam McKegney, Magic Weapons: Aboriginal Writers Remaking Community After Residential School (Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press), viii.

[20] The positive/negative framing is not limited to discussions about sport and recreation. It has surfaced in other areas of research on the residential schools as well. Crystal Fraser and Ian Mosby’s response to Ken Coates’ editorial in the Dorchester Review, wherein Coates argued it was time to focus on something other than the abuse, oppression, and loss of identity that the students encountered, is a case in point. Crystal Fraser and Ian Mosby, “Setting Canadian History Right?: A Response to Ken Coates’ ‘Second Thoughts About Residential Schools,” ActiveHistory.ca, April 2015. (accessed November 14, 2015).

[21] Janice Forsyth and Michael Heine, “‘A Higher Degree of Social Organization’: Jan Eisenhardt and Canadian Aboriginal Sport Policy in the 1950s,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 35, No. 2 (2008), 261-277.

[22] The Indian and Eskimo Residential School Commission of the MSCC cited in Braden TeHiwi, “Physical Culture as Citizenship Education at Pelican Lake Indian Residential School, 1926-1970” (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, 2015), 71.

[23] “All-Indian Team on Ice Warpath: Bantams from Sioux Lookout on Lookout for Scalps,” The Telegram, 13 April 1951.

[24] “12 Indian Puck-Toters Here For Bantam Series,” The Evening Citizen, 12 April 1951.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Indians Impress with Hockey Prowess,” The Ottawa Journal, 14 April 1951.

[27] TeHiwi, 133.

[28] Janice Forsyth and Kevin Wamsley, “‘Championship of Nowhere in Particular’: The Sioux Lookout Black Hawks and the instantiation of Canada’s Residential Schools,” paper presented at the North American Society for Sport History Annual Convention, Green Bay, WI, May 2005.

[29] “Little Native Hockey League” (accessed November 14, 2015).

[30] An excellent starting point for contemplating reconciliation and what it might looks like is Jennifer Henderson and Pauline Wakeham, eds., Reconciling Canada: Critical Perspectives on the Culture of Redress (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Blog posts published before October 28, 2018 are licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License.