By Beth A. Robertson

In late January and early February, the trial of former CBC host Jian Ghomeshi officially began, well over a year since the allegations of sexual assault against Ghomeshi first surfaced. Although this case is considered extraordinary, the trial would seem to be fairly typical of other assault cases, at least in terms of the approach by defence lawyers and media scrutiny. Ghomeshi’s lawyer, Marie Henein, has been likened to Hannibal Lecter in her manner of cross-examination. Her questioning of Lucy DeCoutere and other witnesses during the trial was no exception. Ghomeshi seemed extremely well prepared for this case, in fact, compiling letters, emails and text messages over a thirteen-year period from women who would later accuse him. Ghomeshi’s lawyers effectively wielded these physical and “digital debris” to call into question the women’s credibility, highlighting once more “the gender of lying” as I’ve written on before. The fact that Ghomeshi knew that this strategy of painstaking collection would one day pay off is telling and deserves analysis on its own.

Historians have done their own collecting to reveal just how long this troubling pattern of discrediting women in such cases has been.[1] Laws against sexual and gender-based violence were laid out in Canada’s first Criminal Code of 1892, which stipulated that only women proven to be “of previously chaste character” could receive protection from the justice system. And here was the long-standing qualification that made court cases much more about the female victims than those accused of committing the crime in the first place. Perhaps understandably, many women were deterred from stepping forward as a result, making unreported cases of assault the norm.[2]

A justice system determined to discover “designing women” rather than prosecute raping men was not the only factor that led many women to remain silent.[3] Like we still see in the Ghomeshi case, women often questioned whether their situation was in fact serious enough to seek help from police, and even if they did, the last thing many women wanted was to be shamed by a legal system that was, and perhaps still is, not inclined to believe them. Meanwhile, far too many people, past and present, believe women deserve the violence they receive, especially if they do not conform to cultural stereotypes of the so-called genuine victim.[4]

Historians are perhaps well-situated to see these sort of attitudes enfold, both within and beyond the courtroom, and the subsequent consequences they have, especially for Indigenous, trans, lesbian or bisexual women. This is so even when the historian is by no means looking for it.

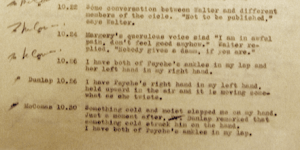

The research for my dissertation, and now forthcoming book, was largely dedicated to what might be called marginal or even pseudoscience, so perhaps it could be argued that the men I studied were in some sense odd or peripheral. Yet many of my subjects were highly esteemed professionals, hailing from Ivy League or otherwise reputable institutions. Although I did not intend to focus on gender-based violence, I was nevertheless affronted again and again by casual references to these supposedly respectable men intentionally injuring, fondling, entrapping, coercing and restraining women against their will.

I had a difficult time processing what I encountered in the archives. Incidents of violence against women seemed to drip from the page, without any recognition of its extremity or frequency. The privilege that these men wielded undoubtedly made their acts seem invisible, normal, even—perhaps not too dissimilar from how Ghomeshi’s long-suspected behaviour was repeatedly ignored or passed over. When I first tried to write about how these men treated certain female subjects, some part of me seemed to shut down as I at least attempted to assume the mantle of the “objective” historian—so much so that a member of my dissertation defence committee took note of it. It was this experience that made me consider more deeply how gender-based violence may in fact pervade the record of the past to a degree that even historians find difficult to come to terms with.

I had a difficult time processing what I encountered in the archives. Incidents of violence against women seemed to drip from the page, without any recognition of its extremity or frequency. The privilege that these men wielded undoubtedly made their acts seem invisible, normal, even—perhaps not too dissimilar from how Ghomeshi’s long-suspected behaviour was repeatedly ignored or passed over. When I first tried to write about how these men treated certain female subjects, some part of me seemed to shut down as I at least attempted to assume the mantle of the “objective” historian—so much so that a member of my dissertation defence committee took note of it. It was this experience that made me consider more deeply how gender-based violence may in fact pervade the record of the past to a degree that even historians find difficult to come to terms with.

The judge in the Ghomeshi case will announce his verdict on March 24th. The results may not be at all satisfactory to his accusers, as some have already predicted, most likely ending in the acquittal that the defence requested of the judge during closing arguments. Regardless of the final outcome, the trial has already “cast a chill” according to advocates of sexual assault victims, reaffirming the culture of silence that remains an integral part of the historical normalization of violence against women.

Beth A. Robertson is a feminist historian and one of the co-editors of ActiveHistory.ca, who teaches with the Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies at Carleton University.

[1] For a few examples, see Terry Chapman, “Sexual Violence in Western Canada, 1890-1920.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Alberta, 1982; Karen Dubinsky, Improper Advances: Rape and Heterosexual Conflict in Ontario, 1880-1929 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993); Constance Backhouse, Carnal Crimes: Sexual Assault Law in Canada (Toronto: The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2008)

[2] Backhouse, 8.

[3] Karen Dubinsky, “‘Maidenly Girls’ or ‘Designing Women’? The Crime of Seduction in Turn-of-the-Century Ontario,” Gender Conflicts: New Essays in Women’s History, eds. Mariana Valverde, Franca Iacovetta (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 27-66

[4] Susan Ehrlich, “Perpetuating—and Resisting—Rape Myths in Trial Discourse,” Sexual Assault in Canada: Law, Legal Practice and Women’s Activism, ed. Elizabeth A. Sheehy, (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2012), 389-408.

A very good piece! thanks!

An excellent job of linking past and present experiences of women before the criminal justice system. I explore similar themes in my book on crime and society in interwar Halifax (City of Order: UBC Press).

Yes, we have to keep reminding everyone of Jian’ s list and also that he was never put on the stand, he never had to endure what any of the witnesses had to endure. For shame, lawyers.