Active History is celebrating its tenth anniversary! As part of our anniversary celebrations we are sharing glimpses of how Active History developed and showcasing our favourite and most popular posts from the past ten years.

Today we are highlighting our most popular post from 2010, written by Karlee Sapoznik this post originally appeared on June 30, 2010. Want to know more about the second year of Active History? See our 2010 year in review post.

Whether it’s a Mars, Cadbury, Hershey, Nestle or Snickers chocolate bar, most of us relish biting into one of life’s most tasty, cheap indulgences: chocolate.

Whether it’s a Mars, Cadbury, Hershey, Nestle or Snickers chocolate bar, most of us relish biting into one of life’s most tasty, cheap indulgences: chocolate.

While the cocoa industry has profited from the use of forced labour in West Africa since the early nineteenth century, over the past decade more and more alarming reports of child slavery in the cocoa industry have come to the fore. Amadou, previously one of the over 200,000 estimated children to be enslaved in cocoa farms in the Ivory Coast alone, told Free the Slaves that “When people eat chocolate, they are eating my flesh.”

The Ivory Coast produces roughly half of the world’s cocoa today. In his recent documentary, entitled The Dark Side of Chocolate , Danish journalist Miki Mistrati seeks to answer the following question: “Is the chocolate we eat produced with the use of child labor and trafficked children?”

In effect, the question is really not whether the chocolate we eat is produced using child labour or trafficked children. Rather, it is twofold: where exactly is this happening and in what numbers? Further, how do we take further measures beyond what is already being done under the law, by the International Cocoa Initiative, the chocolate companies, local law enforcement, activists, the general public and grass roots organizations to truly end this?

The link between slavery and commodities is certainly not new. In the late eighteenth century, the British, like many other countries, directly profited from the slave trade and slavery as they took their tea or used slave-produced products on a daily basis. However, little by little, the London Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade succeeded in rallying popular sentiment against slavery and slave-produced commodities.

For instance, by 1791, thousands were boycotting sugar produced in the Caribbean, an important source of income and profits for much of Britain’s elite. As Adam Hochschild explains in Bury the Chains, “Ignited by several pamphlets, thousands of people, of all ranks and parties stopped using sugar…the boycott was largely put into effect by those who bought and cooked the family food: women.” (192-195). According to Thomas Clarkson’s calculations, no fewer than 300,000 Britons had abandoned the use of slave-produced sugar in the West Indies by 1791. As Clarkson conducted his travels, he reported that there was no town through which he passed in which there was not one person who had stopped using sugar.

Many authors in this time period emphasized the connection between British daily life and that of slaves. Famous poet, Robert Southey, spoke of tea as “the blood-sweetened beverage,” and Sir William Fox urged the tea drinker to “As he sweetens his tea, let him…say as he truly may, this lump cost the poor slave a groan, and this a bloody stroke with a cartwhip.”

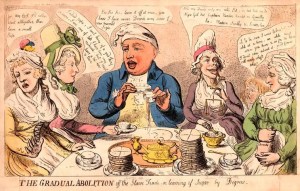

At a time when many citizens could not vote, the sugar boycott provided the underrepresented with a chance to act when Parliament had yet to do so. Isaac Cruikshank’s “The gradual abolition of the slave trade: or leaving of sugar by degrees in 1792” pictured below embodies the outcry against the consumption of slave-produced sugar in England:

Earlier this month, on World Day Against Child Labour on June 12th, renewed calls were made to take action to protect and end the abuses against the children trafficked into and exploited in cocoa farms in Ghana and the Ivory Coast from countries like Mali, Burkina-Faso and Togo.

This map provides a general idea of the source and destination countries involved:

This map provides a general idea of the source and destination countries involved:

Further, on June 14th, the American government released its 2010 Trafficking in Persons Reports. Not surprisingly, according to the Report on Côte d’Ivoire,

“Boys from Ghana, Mali, and Burkina Faso are subjected to forced labor in the agricultural sector, including on cocoa, coffee, pineapple, and rubber plantations; boys from Ghana are forced to labor in the mining sector; boys from Togo are forced to work in construction; and boys from Benin are forced to work in carpentry and construction. Girls recruited from Ghana, Togo, and Benin to work as domestic servants and street vendors often are subjected to conditions of forced labor. Women and girls are also recruited from Ghana and Nigeria to work as waitresses in restaurants and bars and are subsequently subjected to forced prostitution. Trafficked children often face harsh treatment and extreme working conditions.”

Up to 40% of the chocolate we purchase, bring into our homes and eat may be contaminated with slavery. Whether boycotting or “buycotting” chocolate and other slave produced products constitutes part of the answer to resolving this issue remains to be seen. At this point, some argue that there is no way of even knowing for certain if fair trade chocolate is slave free, for there are simply way too many middlemen in the process.

In spite of the lack of consensus on what is the solution, all parties agree that more needs to be done on every front. We need more education, more international pressure, better law enforcement, more preventative measures and more shelters and rehabilitation centres to make those currently enslaved or vulnerable to be enslaved in the cocoa industry slave proof.

We also need more bad press against the chocolate companies and individual farmers who continue to benefit from the dark side of chocolate we literally bite into on a daily basis. History shows us that popular outcry and pressure from below will be essential to this process.

Other websites of interest:

International Labour Rights Forum: The Cocoa Protocol: Success or Failure?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Blog posts published before October 28, 2018 are licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License.