By Timothy J. Stanley

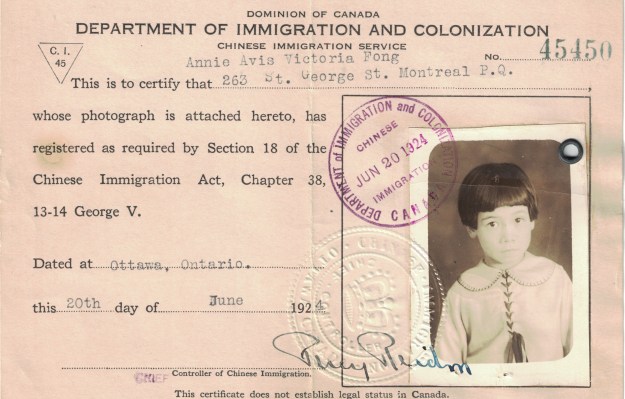

Chinese Immigration Act Certificates of the Fong Sisters and their Mother on Display in the Foyer of the Senate of Canada, Jiaqi Wu, Reflections on Exclusion: An Exhibition on the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923. Exhibit. Senate of Canada, June 5 – June 27, 2023. Photo courtesy of Senator Yuen Pau Woo.

Until its 1947 repeal, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, effectively barred Chinese people from immigrating to Canada and required all Chinese, including the Canadian-born, to register with the government. Failure to register made them liable to fines, imprisonment and deportation. The Chinese are the only group to which such regulations applied. As Henry Yu showed in yesterday’s post, the Act devasted Chinese Canadian communities and permanently marked the Chinese as outsiders who do not belong.

The social structure of racist exclusion behind the Act was integral to the settler colonial project called Canada. Settler colonial invaders convert the territories of Indigenous people into their own private property. During the 1858 Fraser River gold rush, Chinese and Europeans entered the West Coast of what became Canada at the same time. By the mid 1860s, the Chinese were among the largest property owners there and may well have been the majority of the non-Indigenous population. The whole point of establishing a territory in the British Empire was to create the local dominance of people of British origins. Consequently, when British Columbia entered Confederation in 1871, British and Canadian invaders excluded the Chinese as well the Indigenous majority from the new state system called Canada. The third act of the BC legislature disenfranchised the Chinese and blocked Indigenous people from voting. Significantly, other legislation also prevented them from pre-empting land. BC was to be literally the white man’s land, i.e., a territory owned and controlled by a minority of white men.

By 1923 in BC, where the majority of Chinese lived, over 100 laws barred them from voting, from working for the government, for provincially incorporated companies, and from holding crown timber or mining licenses. The Chinese could not become lawyers or pharmacists because they weren’t on the voters’ lists. Municipal regulations often banned them from holding business licenses and from using public facilities such as Victoria’s Crystal Pool. School textbooks taught that the Chinese were foreigners who did not belong. Meanwhile, popular violence had closed entire districts to the Chinese. The Victoria Chamber of Commerce, the Retail Merchants Association of Canada, the Great War Veterans Association, the United Farmers of British Columbia, and the Trades and Labour Council of Canada, all called for Chinese exclusion and for banning them from owning or renting land.

The idea that the Chinese were so different from people of European origins that they could never become “real Canadians” justified this exclusion. For example, in 1885 John A. Macdonald was creating a voting system based on property ownership. He took the vote away from anyone “of Chinese or Mongolian race” for fear that Chinese property owners would control the vote in BC; they then “might enforce those Asiatic principles, those immoralities, . . . which are abhorrent to the Aryan race and Aryan principles” on the House of Commons. He warned that, “like the cross of the dog and the fox,” the Chinese and “Aryan races” could never be amalgamated. A large Chinese migration, he warned, would destroy “the Aryan character of the future of British America . . .” Macdonald’s comments shocked other parliamentarians. Opposition members protested that the Chinese were an “industrious people” who had “as good a right [to] be allowed to vote as any other British subjects of foreign extraction.” When Macdonald’s legislation reached the Senate, his own appointees debated voting it down because of its exclusion of the Chinese.

If in 1885 Chinese alienness was a minority opinion by 1923 it was the absolute truth for most English-speaking Canadians. In the intervening years, prime ministers, official commissioners, academics, journalists, labour organizers, and teachers had repeated the lie that that Canada must be white, and that the Chinese could never integrate. Like the closed loops of social media today, this discourse was itself the product of exclusion; it consisted entirely of white people repeating what other white people said about the Chinese. Chinese Canadian voices were completely ignored.

George Black, the MP for the Yukon and its former Commissioner, showed the link between exclusion and control over territory in his comments in the 1922 House of Commons debate on “Oriental Aliens.” He called the Chinese and Japanese an “invading army” that was “consolidating” its position in BC, Alberta, and Saskatchewan and even Ottawa; he then warned that Canadians would soon be battling these invaders for their very existence. This was not just rhetorical exaggeration; the 2,700 Chinese immigrants to Canada in 1921 were hardly an invasion. Rather, Black was attacking Asians to hide the fact that he himself was the invader. When he entered the Yukon territory during the 1897-9 Klondike Gold Rush, it was controlled by Indigenous peoples and only nominally Canadian. By positioning Asians as invaders, he was legitimizing his own presence in the territory, making himself and other Europeans into natives. i.e., those who properly and naturally belonged, while displacing the Indigenous peoples who had occupied the territory since time immemorial.

In May 1923, before the Chinese could mobilize, the white only members of the House of Commons quickly passed the Exclusion Act. By June the Chinese had formed committees to fight the legislation and sent community leaders to lobby the Senate from as far away as Victoria, BC. Despite their presence in the public gallery as the Senate passed the Act, the Senate called no Chinese witnesses when it studied the bill in special committee. Exclusion was complete.

Despite their exclusion, the Chinese continued to fight for their rights. They mobilized through the network of associations they had built to govern their affairs to protest the Act. From 1923 to 1947 Chinese communities across the country marked July 1st as Humiliation Day, boycotting Dominion Day celebrations. Thousands of Chinese men living in poverty devoted all their resources to maintain their links with families trapped in China. People like Won Alexander Cumyow, the first Chinese born in what became Canada, continued to fight for democratic rights. So too young people also resisted. Such was the case with Montreal’s Fong sisters. Far from being unassimilated, their mother, who come to the country as a 9-year-old orphan in 1893, insisted that they learn the ways of the new country. Born in Canada, they grew up speaking English as their principal language, graduating from Protestant School Board schools, and were active in the Chinese Presbyterian Church. The oldest became an accomplished writer of children’s stories who published in the city’s English language newspapers. The second youngest won scholarships.

C.I.45 Certificate for Annie Avis Victoria Fong.

The baby graduated high school and eventually married a white man. Like many other Chinese in Canada, they showed with the stuff of their lives that they were not alien, that they too had made this country, and that it was their home. I know this because the youngest, Annie, was my mother.

Timothy J. Stanley is an award-winning historian of racism and Chinese Canadian experience. He is currently professor emeritus in the Faculty of Education, University of Ottawa.

Additional Resources

- Clement, Catherine. The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act. 2023. Exhibit. Chinese Canadian Museum, July 1, 2023.

- Denise Fong, John Endo Greenaway, Fran Morrison, John Price, Carmen Rodriguez de France, Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra, and Timothy J. Stanley, 1923: Challenging Racisms Past and Present (Victoria, BC: Canada-China Focus, 2023), http://challengeracism.ca/.

- Timothy J. Stanley, Contesting White Supremacy: School Segregation, Anti-Racism and the Making of Chinese Canadians (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011).

- Timothy J. Stanley, “John A. Macdonald, ‘the Chinese’ and Racist State Formation in Canada,” Journal of Critical Race Inquiry 3, 1 (2016): 6-34.

- Yuen-fong Woon, The Excluded Wife (Montreal and Kingston: McGill Queen’s University Press, 1998).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Blog posts published before October 28, 2018 are licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License.