Ten years ago, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) issued its final report on the history of residential schools in Canada. Mandated to “inform all Canadians about what happened in residential schools”, the “TRC documented the truth of Survivors, their families, communities and anyone personally affected by the residential school experience.” It found that residential schools were part of a broader policy of elimination that was “best described as cultural genocide.”

In 2021, the Canadian Historical Association affirmed the TRC’s findings. The association declared: “…historians, in the past, have often been reticent to acknowledge this history as genocide. As a profession, historians have therefore contributed in lasting and tangible ways to the Canadian refusal to come to grips with this country’s history of colonization and dispossession.” The Canadian Historical Association statement concluded with the following call, “Our inability, as a society, to recognize this history for what it is, and the ways that it lives on into the present, has served to perpetuate the violence. It is time for us to break this historical cycle.”

The findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the self-reflection that followed in many quarters, including amongst the membership of the Canadian Historical Association, highlighted the need for “education for reconciliation”. According to the Commission, “Educating Canadians for reconciliation involves not only schools and post-secondary institutions, but also dialogue forums and public history institutions such as museums and archives. Education must remedy the gaps in historical knowledge that perpetuate ignorance and racism.” Crucially, the Commission noted that “education for reconciliation must do even more.” As the Commission explained, “Survivors told us that Canadians must learn about the history and legacy of residential schools in ways that change both minds and hearts.” (Calls to Action 62, 63, 64).

On this National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, which the federal government created to honour “the children who never returned home and Survivors of residential schools, as well as their families and communities”, members of the Active History editorial collective offer suggestions on scholarship and resources they have found helpful in their own work and learning journeys.

Sara Wilmshurst

If it was up to me, every settler would watch the National Film Board documentary PowWow at Duck Lake. The NFB included it in an “experimental” series of films featuring “strong and often purely personal viewpoints” to “stimulate discussion”. The fourteen-minute film compiles footage from the Indian-Métis Jamboree held at St. Michael’s Residential School in Duck Lake, Saskatchewan in 1967. Children and adults alike gathered to hear music and jokes; one speaker quipped that “freedom has no colour – it’s pure white.” The event also featured remarks from activists Howard Adams, Harold Cardinal, and Mary Ann Lavallée.

On the premises of a long-standing residential school Adams openly called the system “apartheid.” Audience members spoke about the violence they survived in residential schools (intercut with footage of an awkward priest in the back of the auditorium). The last portion of the documentary shows the priest confronted by activists and a young man who left residential school in grade 9. Watching the priest flap between defensiveness, cruel sarcasm, and arrogance may cause you to chew through a pencil, but the (unfortunately unnamed) young man held his ground. His perceptive words remind us of the work yet to do combatting denialism. “Immediately, when an Indian asks a question the hostility isn’t on the Indian’s part, it’s on the people being questioned, because they have the guilty conscience, and they are the ones who are insecure about what they’re doing.”

Laura Madokoro

For me, “education for reconciliation” involves thinking about the places and institutions to which I am attached and how they are marked by or perpetuate histories of colonialism and displacement. I think the local context is an important starting point. My suggestion, Harold Cardinal’s The Unjust Society reflects one example of this. The Unjust Society, Cardinal’s response to the 1969 White Paper, is a searing critique of the federal government’s policies vis-à-vis First Nations in Canada. Cardinal opens with, “The history of Canada’s Indians is a shameful chronicle of the white man’s disinterest, his deliberate trampling of Indian rights and his repeated betrayal of our trust. Generations of Indians have grown up behind a buckskin curtain of indifference, ignorance and, all too often, plain bigotry. Now at a time when our fellow Canadians consider the promise of the Just Society, once more the Indians of Canada are betrayed by a programme which offers nothing better than cultural genocide.”

Re-reading The Unjust Society in 2025 remarkable for the ways in which many of the present concerns were already being voiced decades ago (and Cardinal himself was building on earlier expressions of concern and activism). Moreover, I didn’t realize until recently that Cardinal (whom Sara Wilmburst also mentions in her comments) was an MA student at St. Patrick’s College at Carleton University where I now teach. I am reading it now as an opportunity to think about Cardinal’s arguments in a very local context to further my understanding of place as well as Indigenous resistance.

Mack Penner

In my day job as a historian of conservatism in Canada, part of what I study is how right-wing intellectuals and political actors have defended, and sought to extend, the settler colonial project in Canada. On the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, as we are asked not just to acknowledge but to redress the history of residential schools, it is impossible not to note and lament the purchase that residential school denialism has in these circles and beyond. Residential school denialism is, then, one aspect of a broader project to render Canadian history in selective and convenient ways that make it possible not just to present historical colonization in rosy terms but to argue for the extension of that colonization in the present via the expansion of settler institutions like private property rights. In other words, in Canada today the misuse of history to justify assimilationist settler ideology is an ongoing reality.

This being the case, the text I want to recommend is Sarah Carter and Nathalie Kermoal’s “Property Rights on Reserves: ‘New’ Ideas from the Nineteenth Century,” a chapter from a recent edited collection called Creating Indigenous Property: Power, Rights, and Relationships. I recommend a chapter from a pricey academic book with some reluctance, but in any case what’s so useful about this chapter is that Carter and Kermoal document not just the contemporary phenomenon that I’ve described here but also, in detail, how and why those convenient right-wing histories go wrong.

Alex Gagné

I recommend Sean Carleton’s Lessons in Legitimacy: Colonialism, Capitalism, and the Rise of State Schooling in British Columbia. As a historian of childhood and youth justice in Canada, this book has profoundly shaped how I understand the colonial project of education and childcare. Carleton’s deliberate structural choice, organizing chapters to show the parallel yet oppositional systems of Indigenous and settler education, powerfully exposes the colonial project’s calculated nature. By placing Day Schools, Industrial Schools, and Residential Schools alongside public education for settler children, he reveals not just the disparities between haves and have-nots but the Canadian government’s systematic design to entrench these divisions. The juxtaposition makes visible how education functioned as a tool of dispossession and assimilation for Indigenous children while simultaneously preparing settler children for citizenship and opportunity within the colonial state.

Beyond its historical insights, Lessons in Legitimacy offers an invaluable model of how settler historians can engage ethically with Indigenous histories. Carleton centers the voices and experiences of Survivors throughout, ensuring their testimonies shape our understanding of this history – not as abstract policy, but as lived trauma and resilience. He demonstrates what conscientious scholarship looks like: transparent about his own positionality, rigorous in his engagement with Indigenous methodologies, and deeply respectful in handling Indigenous voices and knowledge systems. In my own learning journey, this approach has been essential; it remedies gaps in historical knowledge while helping me grapple with the ongoing legacies of residential schools. His methodological care provides a blueprint for settler scholars and shows readers what accountability looks like in practice.

Thomas Peace

The TRC’s final report changed my scholarship. Completed just a year after I took up my position as the Canadian Historian at Huron University College, the six volume report – and its 94 Calls to Action – resonated strongly. As one of the first post-secondary institutions in southwestern Ontario, Huron – an Anglican seminary then – must have had – I thought – some connection to the operation of the region’s two residential schools: the Mohawk Institute and the Mount Elgin Institute. But this was seemingly not the case. Aside from a reference to two of Huron’s early Indigenous graduates – Kesheqowenene (John Jacobs, Anishinaabe) and Isaac Bearfoot (Onondaga) – the school’s history was silent on the subject.

This got me digging. Since then, working through Huron’s Community History Centre, we’ve sought to better understand these connections. We now have a much deeper understanding of Huron’s relationship to these schools. We learned, for example, that Huron, Western University, and the Shingwauk Residential School were build upon the same social, political, and economic networks. This has led to a deeper study of how Indigenous individuals, communities, and nations engaged with Huron and Western over their 160+ year history. It also led to the publication earlier this month of the new book, Behind the Bricks: The Life and Times of the Mohawk Institute, Canada’s Longest-Running Residential School, a joint project led by Rick Hill that provides the most comprehensive history to date of Canada’s oldest and longest running residential school.

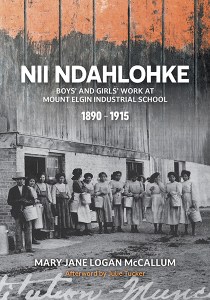

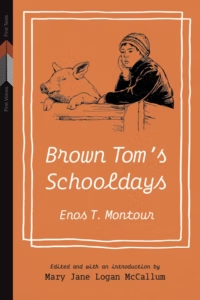

The collaborative nature of each of these projects demonstrates that we are not doing this work alone. In addition to the projects we have been running at Huron, University of Winnipeg Canada Research Chair Mary Jane Logan McCallum has been busy developing our understanding of the Mount Elgin Institute, a Methodist/United Church-run residential school about 35 kilometres from London. Last year, she published Brown Tom’s School Days, a fictionalized memoir of Enos Montour’s experiences at Mount Elgin; the year before, she published Nii Ndahlohke: Boys and Girls Work at the Mount Elgin Industrial School.

Taken together, and building upon Elizabeth Graham’s seminal 1997 book on the two schools, these works have helped deepen our understanding of the residential school experience in southwestern Ontario. They would have been impossible to produce without the foundation laid by the TRC and the long legacy of Indigenous activism that brought the commission about.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Blog posts published before October 28, 2018 are licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada License.