Pedro Rafael González Chavajay, a Tz’utuhil-Maya from San Pedro la Laguna. Used with permission from him and Artemaya.

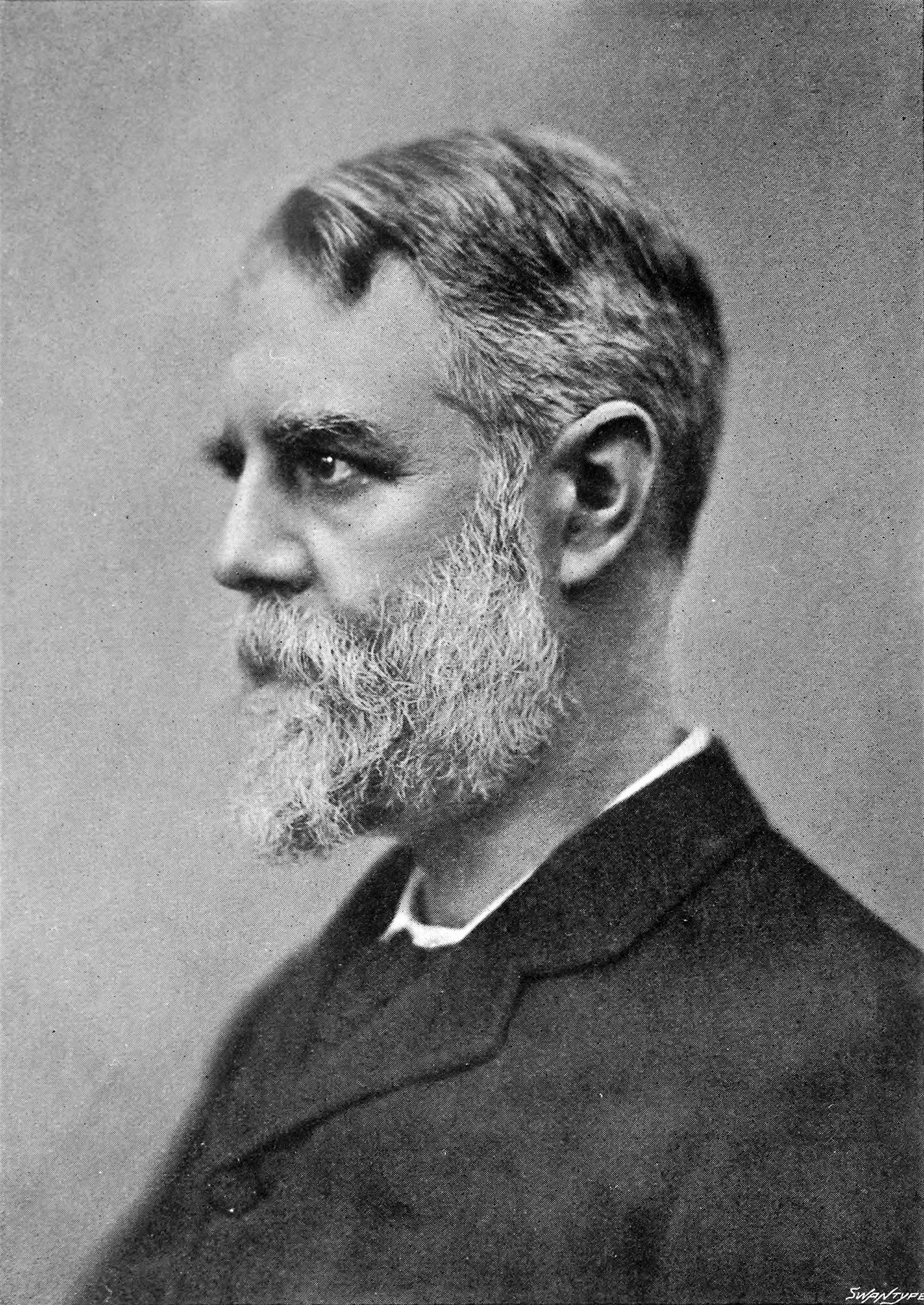

Jim Handy

As summer winds down I have been slowly catching up on reading avoided while happily engaged elsewhere. This includes back copies of The Economist. As always reading The Economist prompts an appreciation for their insightful reporting on some issues and their tone-deaf, ahistorical and simply wrong accounts on others.

The July 1st, 2023 edition had a briefing entitled “Out of the Frying Pan” filed from Cairo, Chattogram (Bangladesh), and Niamey (Niger). In this story the author (anonymous as is the practice in the paper) appropriately warned that peasants in some of the poorest areas of the world are likely to suffer the worst consequences from climate change. As global warming intensifies and their lands and livelihoods suffer, they will make up a significant portion of the millions of climate refugees. Already, The Economist notes, rural livelihoods have been made more precarious by conflicts created or exaggerated by climate change.[1]

But it is exactly here that the author finds a silver lining. The author suggests, “Climate change may jolt some into making a decision (to migrate) that would long have been in their interest anyway.” If climate change accelerates rural to urban migration and induces more peasants and small farmers to give up their land more quickly, the paper predicts, “they will probably find better work, health care and schools. They may also start having smaller families.” The task of feeding the world, including new migrants to urban areas, will need to “rely on bigger, more capital-intensive farms.”

In making such an argument, the paper is at least reliably consistent. Since its birth in 1843, the paper has unfailingly championed large, capital-intensive farming and counselled that small farmers and peasants be forced to abandon the countryside and flee to the cities as the natural (and beneficial) consequence. In the second edition of the paper in September 1843 the paper celebrated the fact that the “science of agriculture” was replacing the “art of husbandry” in the English countryside and in the process modern farmers employing capital were “breaking up the hard clods of ignorance, sloth and indifference.” [2] From that point, the paper steadfastly argued that the most pressing problem in English agriculture was “how can capital be attracted to the soil?”[3] Continue reading →